He rose to football glory and amassed billions in film. His trial for the murders of his former wife and her companion marked a watershed moment in American race relations.

O.J. Simpson, who rose to prominence on the football field, amassed billions as an all-American in movies, television, and advertising, and was acquitted of murdering his estranged wife and her friend in a 1995 Los Angeles trial that captivated the nation, died on Wednesday at his Las Vegas home. He was 76.

His family confirmed on social media that the cause was cancer.

The murder trial jury acquitted him, but the case, which served as a fractured mirror for Black and white America, altered the course of his life. In 1997, a civil suit filed by the victims’ families found him accountable for the deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald L. Goldman, ordering him to pay $33.5 million in damages. He paid off little of his debt, relocated to Florida, and fought to rebuild his life, raise his children, and keep out of trouble.

In 2006, he sold a book manuscript called “If I Did It,” as well as a planned TV appearance in which he gave a “hypothetical” narrative of murders he had always denied doing.

He was arrested in 2007 when he and several guys broke into a sports memorabilia dealer’s hotel room in Las Vegas and stole a trove of artifacts. He claimed the items were taken from him, but in 2008, a jury found him guilty of 12 crimes, including armed robbery and kidnapping, following a trial attended by barely a few media and onlookers. He was sentenced to nine to 33 years in Nevada’s state prison. He completed the minimum sentence and was freed in 2017.

Over the years, the narrative of O.J. Simpson sparked a flood of tell-all books, movies, studies, and discussion on issues of justice, race relations, and celebrity in a country that idolizes its heroes.

There were numerous in the Simpsons series. Yellowing old newspaper clippings reveal the first portraits of a postwar child of poverty, afflicted with rickets and forced to wear steel braces on his spindly legs, of a hardscrabble life in a bleak housing project, and of hanging out with teenage gangs in San Francisco’s tough back streets, where he learned to run.

“Running, man, that’s what I do,” he declared in 1975, when he was one of America’s best-known and highest-paid football players, the Buffalo Bills’ electric, swivel-hipped ball carrier affectionately known as the Juice. “All my life I’ve been a runner.”

And so he had spent 11 years running to daylight on the gridiron of the University of Southern California and in the roaring stadiums of the National Football League; running for Hollywood movie moguls, Madison Avenue image-makers, and television networks; and running to the pinnacles of success in sports and entertainment.

Along the way, he set collegiate and professional records, won the Heisman Trophy, and was inducted into the pro football Hall of Fame. He featured in dozens of films and famous commercials for Hertz and other companies, worked as a sports analyst for ABC and NBC, bought homes, vehicles, and a beautiful family, and became an American idol — a handsome warrior with the kind eyes and soft voice of a lovely guy. He also played golf.

On the surface, it seemed like the ideal life. But there was a deeper, more troubled reality—about an infant daughter drowning in the family pool and a divorce from his high school sweetheart; about his stormy marriage to a stunning young waitress and her frequent calls to the police when he beat her; about a frustrated man’s jealous rages.

Calls to the Police

Nicole Simpson was repeatedly bruised and terrified as a result of the abuse, but police rarely took action. On New Year’s Day, 1989, policemen discovered her severely battered and half-naked in the bushes outside their home after receiving a single call. “He’s going to kill me!” she cried. Mr. Simpson was arrested and convicted of spousal abuse, but was released with a fine and probation.

The couple split in 1992, but disagreements persisted. On October 25, 1993, Ms. Simpson phoned the police again. “He’s back,” she told the 911 operator, prompting authorities to intercede once more.

Then something happened. On June 12, 1994, Ms. Simpson, 35, and Mr. Goldman, 25, were attacked outside her condominium in Brentwood, Los Angeles, near Mr. Simpson’s mansion. She was nearly decapitated, while Mr. Goldman was cut to death.

The knife was never located, but investigators discovered a bloodied glove and other hair, blood, and fiber traces. Investigators suspected Mr. Simpson, 46, was the killer from the outset, despite being aware of his previous abuse and her calls for help. They discovered blood on his car and a bloody glove in his home, which matched the one found near the bodies. There were never any additional suspects.

Five days later, after attending Nicole’s funeral with their two children, Mr. Simpson was charged with murder but fled in his white Ford Bronco.With his old friend and teammate Al Cowlings at the wheel and the fugitive in the back holding a gun to his head and threatening suicide, the Bronco led a convoy of patrol cars and TV helicopters on a sluggish 60-mile televised chase over Southern California freeways.

Networks preempted prime-time programming for the event, which was filmed in part by news cameras mounted on helicopters, and a countrywide audience of 95 million people watched for hours. Overpasses and roadsides were packed with spectators. The police halted highways, and motorists gathered to watch, some waving and cheering at the passing Bronco, which did not stop. Mr. Simpson eventually went home and was arrested.

The subsequent trial, which lasted nine months, from January to early October 1995, captivated the nation with its graphic accounts of the murders, as well as the tactics and strategy of prosecutors and a defense team that included the “dream team” of Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., F. Lee Bailey, Alan M. Dershowitz, Barry Scheck, and Robert L. Shapiro.

The prosecution, led by Marcia Clark and Christopher A. Darden, had what appeared to be overwhelming evidence: tests showing that blood, shoe prints, hair strands, shirt fibers, carpet threads, and other items found at the murder scene had come from Mr. Simpson or his home, as well as DNA tests proving that the bloody glove found at Mr. Simpson’s home matched the one left at the crime scene.

Prosecutors also possessed a list of Mr. Simpson’s 62 incidences of abusive behavior with his wife.

However, as the trial progressed before Judge Lance Ito and a 12-member jury that comprised ten Black persons, it became clear that the police investigation had been defective. Photo evidence had been lost or mislabeled; DNA had been obtained and kept incorrectly, suggesting the potential that it was contaminated. Detective Mark Fuhrman, a key witness, admitted that he entered the Simpson home and discovered the matching glove and other critical evidence without a search warrant.

‘If the Glove Don’t Fit’

The defense claimed, but never proved, that Mr. Fuhrman planted the second glove. More harmful, however, was its attack on his racist past. Mr. Fuhrman insisted that he had not used racist words in a decade. However, four witnesses and a taped radio conversation shown for the jury contradicted him, undermining his credibility. (After the trial, Mr. Fuhrman pleaded no contest to perjury charges. He was the only one convicted in the case.

In what was regarded as the trial’s pivotal error, the prosecution requested Mr. Simpson, who was not called to testify, to try on gloves. He strained to do so. They were evidently too small.

“If the glove does not fit, you must acquit,” Mr. Cochran told the jury later.

In the end, the defense had the strongest case, with numerous reasons for reasonable doubt, the requirement for acquittal. But it wanted more. It accused the Los Angeles police of racism, claimed that a Black man was railroaded, and encouraged the jury to look beyond guilt or innocence and send a message to a racist culture.

On the day of the verdict, autograph seekers, T-shirt merchants, street preachers, and paparazzi crowded the courthouse steps. Following what some news media sites labeled “The Trial of the Century,”.

Despite producing 126 witnesses, 1,105 items of evidence, and 45,000 pages of transcripts, the jury deliberated for barely three hours after being sequestered for 266 days, the longest in California history.

Much of America came to a stop. People paused to watch in their homes, offices, airports, and shopping malls. Even President Bill Clinton exited the Oval Office to join his secretaries. Cries of “Yes!” and “Oh, no!” reverberated across the country as the ruling left many Black people ecstatic and many white people shocked.

In the aftermath, Mr. Simpson and the case inspired television specials, documentaries, and more than 30 books, many of which were written by individuals who made millions.

Mr. Simpson collaborated with Lawrence Schiller on “I Want to Tell You,” a thin mosaic volume of letters, images, and self-justifying commentary that sold hundreds of thousands of copies and made him more than $1 million.

He was released after 474 days in captivity, but his experience was far from done. The Goldman and Brown families rehashed much of the case in their civil lawsuit. A mostly white jury, using a lighter standard of proof, found Mr. Simpson guilty and awarded the families $33.5 million in damages. The legal action, which eliminated racial factors as inflammatory and speculative, provided a form of vindication for the families while also dealing a blow to Mr. Simpson, who vowed that he would never pay the damages.

Mr. Simpson had spent a lot of money on his criminal defense. According to records produced in the murder trial, his net worth was over $11 million, but sources familiar with the matter say he currently has only $3.5 million. A 1999 auction of his Heisman Trophy and other artifacts raised around $500,000 for the plaintiffs. However, court documents reveal that he paid only a small portion of the outstanding debt.

He regained custody of the children he had with Ms. Simpson, and in 2000 he relocated to Florida, purchased a property south of Miami, and settled into a quiet existence, playing golf and living on pensions from the NFL, the Screen Actors Guild, and other sources, totaling around $400,000 per year.

Although the glamour and lucrative contracts were gone, Mr. Simpson sent his two children to prep school and college. He was seen in restaurants and malls, where he gladly signed autographs. He received two fines: one for speeding in a manatee zone and another for pirating cable television signals.

In 2006, as the debt to the murder victims’ families grew to $38 million with interest, he was sued by Fred Goldman, Ronald Goldman’s father, who claimed that his book and television deal for “If I Did It” had advanced him $1 million and was designed to defraud the family of the damages owed.

The projects were canceled by News Corporation, which owns HarperCollins and the Fox Television Network, and a spokesman said Mr. Simpson was not expected to repay a $800,000 advance. Following a bankruptcy court proceeding, the Goldman family obtained the book rights from a trustee and published it in 2007 under the title “If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer.” The book’s cover included the words “If” in small print and “I Did It” in bold red letters.

Another Trial, and Prison

In 2008, after years of appearing to have been convicted in the court of public opinion, Mr. Simpson faced a jury once more. This time, he was accused of entering a Las Vegas hotel room in 2007 with five other men, the majority of whom were convicted criminals and two of whom were armed, in order to take a wealth of sports memorabilia from two collectible dealers.

Mr. Simpson said that he was just seeking to recover stolen items from him, such as eight footballs, two plaques, and a portrait of himself with F.B.I. director J. Edgar Hoover, and that he had no knowledge of any guns. However, four individuals who had been detained with him and pleaded guilty testified against him, with two claiming they had carried firearms at his instruction. Prosecutors also showed hours of secretly recorded tapes by a co-conspirator that detailed the crime’s preparation and execution.

On October 3, 13 years to the day after his acquittal in Los Angeles, a jury of nine women and three men convicted him of armed robbery, kidnapping, assault, conspiracy, coercion, and other offenses.

After Mr. Simpson was sentenced to at least nine years in jail, his lawyer promised to appeal, noting that none of the jurors were Black and asking whether they could be fair to Mr. Simpson given what had happened years before. However, jurors stated that the double-murder case was never referenced during deliberations.

In 2013, the Nevada release Board granted Mr. Simpson release on multiple offenses linked to his robbery conviction, citing his good behavior in prison and involvement in inmate activities. However, the board left other verdicts in place. A Nevada judge denied his request for a new trial, and legal experts predicted that appeals were unlikely to be successful.

Mr. Simpson’s parole requirements, such as travel limitations, no communication with co-defendants in the robbery case, and no excessive drinking, remained in effect until 2021, when they were lifted, allowing him to be entirely free.

Questions regarding his guilt or innocence in the murders of his ex-wife and Mr. Goldman persisted. In May 2008, Mike Gilbert, a memorabilia dealer and former buddy, wrote in a book that Mr. Simpson, high on marijuana, confirmed to him the killings during the trial. Mr. Gilbert described Mr. Simpson as saying that he did not carry a knife but utilized one that Ms. Simpson was holding when she opened the door.

More than 20 years after his murder conviction, O.J. Simpson’s story was recounted twice more on television in 2016, continuing to captivate large crowds. “The People v. O.J. Simpson,” Ryan Murphy’s chapter in the “American Crime Story” anthology on FX, centered on the trial itself and the cast of characters brought together by the defendant (Cuba Gooding Jr.). “O.J.: Made in America,” a five-part, nearly eight-hour installment in ESPN’s “30 for 30” documentary series (which was also released in theaters), detailed the trial but expanded the narrative to include a biography of Mr. Simpson as well as an examination of race, fame, sports, and Los Angeles over the previous 50 years.

In a commentary in The New York Times, A.O. Scott called “The People v. O.J. Simpson” a “tightly packed, almost indecently entertaining piece of pop realism, a Dreiser novel infused with the spirit of Tom Wolfe” and said “O.J.: Made in America” had “the grandeur and authority of the best long-form fiction.”

In Leg Braces as a Child

Orenthal On July 9, 1947, James Simpson was born in San Francisco as the fourth child of James and Eunice (Durden) Simpson. As a newborn with calcium deficient rickets, he wore leg braces for several years until outgrowing his handicap. His father, a janitor and cook, abandoned the family when the child was four, and his mother, a hospital nurse’s assistant, reared the children in a housing project in the difficult Potrero Hill neighborhood.

As a youth, Mr. Simpson, who loathed the name Orenthal and went by O.J., ran with street gangs. But when he was 15, a friend introduced him to Willie Mays, the famed San Francisco Giants outfielder. Mr. Simpson described the event as inspirational and life-changing. He joined the Galileo High School football team and earned All-City recognition in his final year.

In 1967, Mr. Simpson married Marguerite Whitley, his high school sweetheart. The couple has three children: Arnelle, Jason, and Aaren. Aaren, 23 months old at the time of their divorce in 1979, slipped into a swimming pool at home and died a week later.

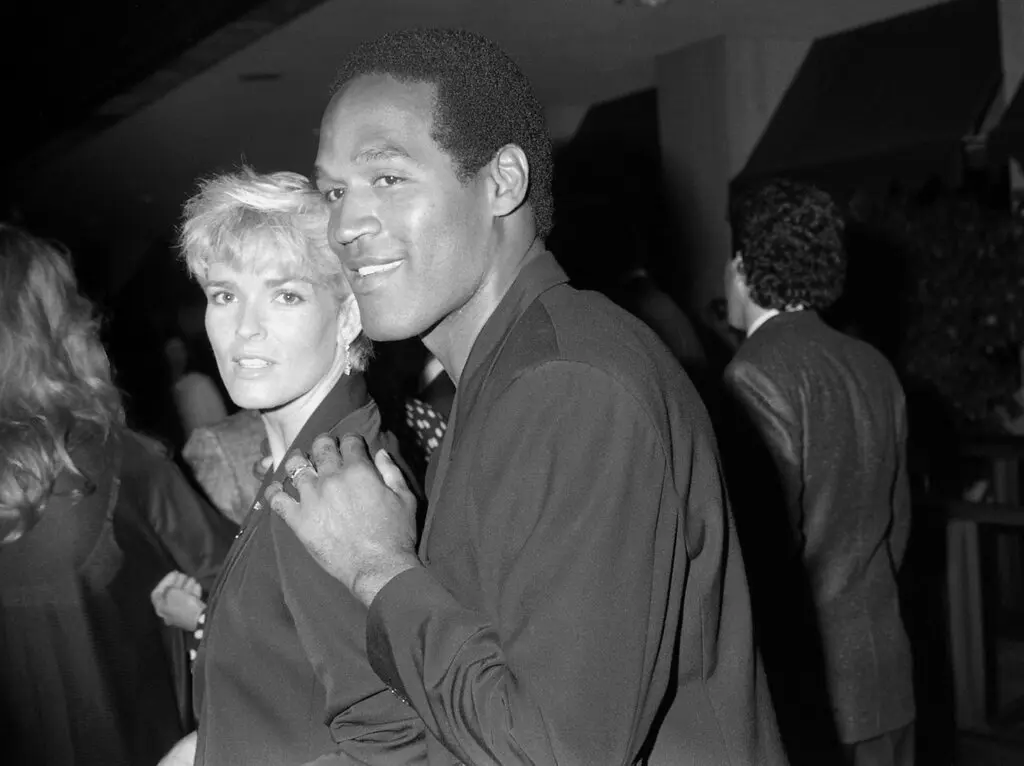

Mr. Simpson married Nicole Brown in 1985, and the couple had a daughter, Sydney, and son, Justin. He is survived by his children Arnelle, Jason, Sydney, and Justin Simpson, as well as three grandkids, according to his lawyer Malcolm P. LaVergne.

After being released from jail in Nevada in 2017, Mr. Simpson moved into the Las Vegas country club home of a rich acquaintance, James Barnett, for what he thought would be a brief visit. However, he found himself enjoying the local golf scene and establishing acquaintances, sometimes with people who approached him at restaurants, according to Mr. LaVergne. Mr. Simpson decided to stay in Las Vegas full-time. He died while living right on the Rhodes Ranch Golf Club’s course.

Mr. Simpson was a natural football player from a young age. He had incredible speed, power, and skill in a broken field, making him difficult to catch, let alone tackle. He started his college career at San Francisco City College and scored 54 touchdowns in two years. In his third year, he transferred to Southern California, where he broke records, rushing for 3,423 yards and 36 touchdowns in 22 games and leading the Trojans to the Rose Bowl in consecutive seasons. In 1968, he was named the finest college football player in the country, earning the Heisman Trophy. Some magazines referred to him as the greatest running back in college football history.

His professional career was even more illustrious, however it took awhile to get started. Mr. Simpson, the first pick in the 1969 draft, went to the Buffalo Bills, the league’s weakest team, and was utilized little in his first season before being sidelined with a knee injury in his second. However, he began busting games open in 1971, behind a line known as the Electric Company because they “turned on the Juice.”

In 1973, Mr. Simpson became the first player in NFL history to rush for over 2,000 yards, shattering Jim Brown’s record, and was named the league’s MVP. In 1975, he topped the American Football Conference in rushing and scoring. After nine seasons, he was traded to his hometown team, the San Francisco 49ers, where he spent his final two seasons. He retired in 1979 as the league’s highest-paid player, with a salary of over $800,000, after scoring 61 touchdowns and rushing for over 11,000 yards in his career. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985.

Actor and Pitchman

He also pursued a career in acting. He appeared in approximately 30 films and television productions, including the mini-series “Roots” (1977), the films “The Towering Inferno” (1974), “Killer Force” (1976), “Cassandra Crossing” (1976), “Capricorn One” (1977), “Firepower” (1979), and others, including the comedy “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad” (1988) and its two sequels.

He didn’t pretend to be a serious actor. “I’m a realist,” he explained. “No matter how many acting lessons I took, the public just wouldn’t buy me as Othello.”

Mr. Simpson was a likable celebrity. He spoke freely with reporters and fans, signed autographs, posed for pictures with children, and was humble in interviews, praising his colleagues and coaches, who clearly admired him. In an era of Black power demonstrations, his only militancy was to smash heads on the gridiron.

His smiling, racially neutral appearance, easygoing demeanor, and nearly universal acceptance made him an ideal candidate for endorsements. Even before joining the NFL, he negotiated contracts, including a three-year, $250,000 deal with Chevrolet. He later promoted sports equipment, soft drinks, razor blades, and other products.

In 1975, Hertz cast him as the first Black star in a national television commercial. Memorable long-running advertising showed him rushing through airports and leaping over counters to get to a Hertz rental car. He made millions, Hertz rentals skyrocketed, and the advertisements made O.J.’s face one of the most known in America.

Mr. Simpson penned his own farewell on the day of his arrest. While riding in a Bronco with a gun to his head, a friend, Robert Kardashian, issued a handwritten letter to the public that he had left at home, expressing love for Ms. Simpson and denying that he killed her.